Save Your Knees

What You Need to Know About Meniscus Tears

The meniscus plays a crucial role in joint function, acting as a protective structure that prevents the deterioration and degeneration of articular cartilage. It is vital in reducing the risk of osteoarthritis by disturbing loads and providing stability to the knee joint. Six decades ago, it was discovered that removing the meniscus – a common practice at the time – led to cartilage deterioration and gradually contributed to arthritis. This finding drastically changed the approach to treating meniscus-related injuries.

Anatomy of the Meniscus:

The knee joint contains two menisci: the medial and lateral meniscus. These crescent-shaped fibrocartilaginous structures are situated between the corresponding femoral condyle and tibial plateau. Several stabilizing ligaments, including the medial collateral ligament, the transverse ligament, the meniscofemoral ligaments, and attachments at the anterior and posterior horns, contribute to meniscal stability.

The meniscus is divided into three vascular zones that influence its healing potential:

-

The red-red zone (outer third): Well-vascularized, with a greater potential for healing.

-

The red-white zone (middle third): Moderately vascularized, with limited healing potential.

-

The white-white zone (inner third): Avascular, with minimal capacity for self-repair.

Classification of Meniscus Tears:

Meniscal injuries are categorized based on location, thickness, and stability:

1. Vascular Zones:

-

Red-red tears (peripheral vascularised portion)

-

Red-white tears (middle third, transitional zone)

-

White-white tears (inner avascular portion)

2. Depth of Tear:

-

Partial-thickness tears

-

Full-thickness tears (further classified as stable or unstable)

3. Tear Patterns:

-

Vertical/Longitudinal (including bucket-handle tears)

-

Radial/Transverse tears

-

Oblique/Flap tears

-

Horizontal/Complex tears (including degenerative tears)

Understanding the classification is crucial for selecting the most appropriate treatment. Studies indicate that meniscal tear patterns differ significantly between stable knees and those with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries.

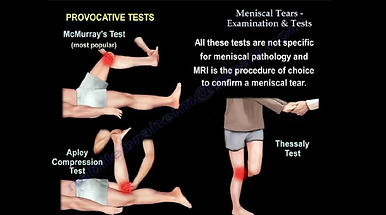

Diagnosis of Meniscal Injuries:

A comprehensive patient history, physical examination, and imaging techniques help in diagnosing meniscal tears.

-

Patient Symptoms: Pain, swelling, and joint locking.

-

Physical Examination: Joint effusion, joint line tenderness

-

Diagnostic Tests:

-

Joint line palpation

-

McMurray’s test (pain or clicking on knee flexion/extension)

-

Apley’s grind test (pain with compression/rotation)

-

Thessaly test (pain during single-leg stance with rotation)

-

MRI is the gold standard for confirming meniscal injuries, providing detailed visualization of the tear location and severity.

Treatment options:

Meniscus tears are managed either non-operatively or surgically, depending on patient factors and tear characteristics.

Non-operative Management

Non-surgical treatment is typically reserved for:

-

Degenerative tears in older adults (>40 years) without mechanical symptoms.

-

Small, stable tears in the vascularised region.

-

Conservative Therapy:

-

Exercise therapy (quadriceps and hamstring strengthening).

-

Manual therapy (indirect osteopathic techniques).

-

Cryotherapy (RICE protocol).

-

Evidence suggests that in patients with knee degeneration, structured physical therapy is equally effective as meniscectomy in improving function and reducing pain.

Surgical Management

Surgical options include:

1. Meniscectomy (Partial or Total):

-

Performed when repair is not feasible.

-

Higher risk of osteoarthritis with total meniscectomy.

2. Meniscus Repair:

-

Preferred in younger patients (<40 years) with peripheral, reducible tears.

-

80% success rate at two years postoperatively.

-

Techniques:

-

Inside-out sutures

-

Outside-in sutures

-

All-inside sutures

-

3. Meniscus Transplantation (Allograft or Scaffold):

-

Considered for patients with significant meniscus loss.

-

Limitations include graft preservation, viral transmission, and mismatching.

Studies indicate that lateral meniscus repairs have lower failure rates than medial meniscus repairs due to differences in biomechanical loading and attachment stability.

Postoperative Rehabilitation

Rehabilitation protocols vary from restricted weight-bearing approaches to accelerated programs with early mobilisation. Studies suggest:

-

Accelerated rehabilitation with partial or full weight-bearing and knee motion up to 90° is effective.

-

Strength training (quadriceps and hamstring exercises) is essential for long-term knee stability.

-

Physiotherapy plays a key role in reducing symptoms, restoring function, and preventing secondary quadriceps atrophy.

Meniscal injuries are common in both athletes and aging individuals. The choice between conservative and surgical treatment depends on multiple factors, including tear location, severity, and patient characteristics. While meniscus repair is the preferred option in young, active patients, degenerative tears in older adults may be managed effectively with structured rehabilitation. Postoperative rehabilitation strategies should focus on restoring knee function while minimizing re-injury risks.

References

-

Arnoczky, S. P. and Warren, R. F., ‘Microvasculature of the human meniscus’, American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 10, no. 2, 1982, pp. 90-95.

-

Petersen, W. and Tillmann, B., ‘Collagenous fibril texture of the human knee joint menisci’, Anatomy and Embryology, vol. 197, no. 4, 1998, pp. 317-324.

-

Noyes, F. R. and Barber-Westin, S. D., ‘Meniscus tears: Diagnosis and treatment’, The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, vol. 98, no. 6, 2016, pp. 555-565.

-

Bollen, S. R., ‘Meniscal injuries in the cruciate-deficient knee’, The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery (Br), vol. 72, no. 4, 1990, pp. 674-676.

-

Karachalios, T. et al., ‘Diagnostic accuracy of the Thessaly test for meniscal tears’, The Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery (Am), vol. 87, no. 5, 2005, pp. 955-962.

-

Behairy, N. H. et al., ‘Accuracy of routine MRI in meniscal and ligamentous injuries of the knee’, The Egyptian Journal of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, vol. 45, no. 4, 2014, pp. 1153-1162.

-

Logerstedt, D. S. et al., ‘Knee pain and mobility impairments: Meniscal and articular cartilage lesions’, Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 40, no. 6, 2010, pp. A1-A35.

-

Katz, J. N. et al., ‘Surgery versus physical therapy for meniscal tears’, New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 368, no. 18, 2013, pp. 1675-1684.

-

Pujol, N. et al., ‘Meniscal repair’, Orthopaedics & Traumatology: Surgery & Research, vol. 101, no. 1, 2015, pp. S85-S94.

-

Rodeo, S. A., ‘Meniscus transplantation’, Sports Medicine and Arthroscopy Review, vol. 18, no. 3, 2010, pp. 197-202.

-

Sherman, M. F. et al., ‘Meniscus repair’, American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 19, no. 3, 1991, pp. 215-218.

-

Kocabey, Y. et al., ‘Rehabilitation following meniscal repair’, Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, pp. 57-65.